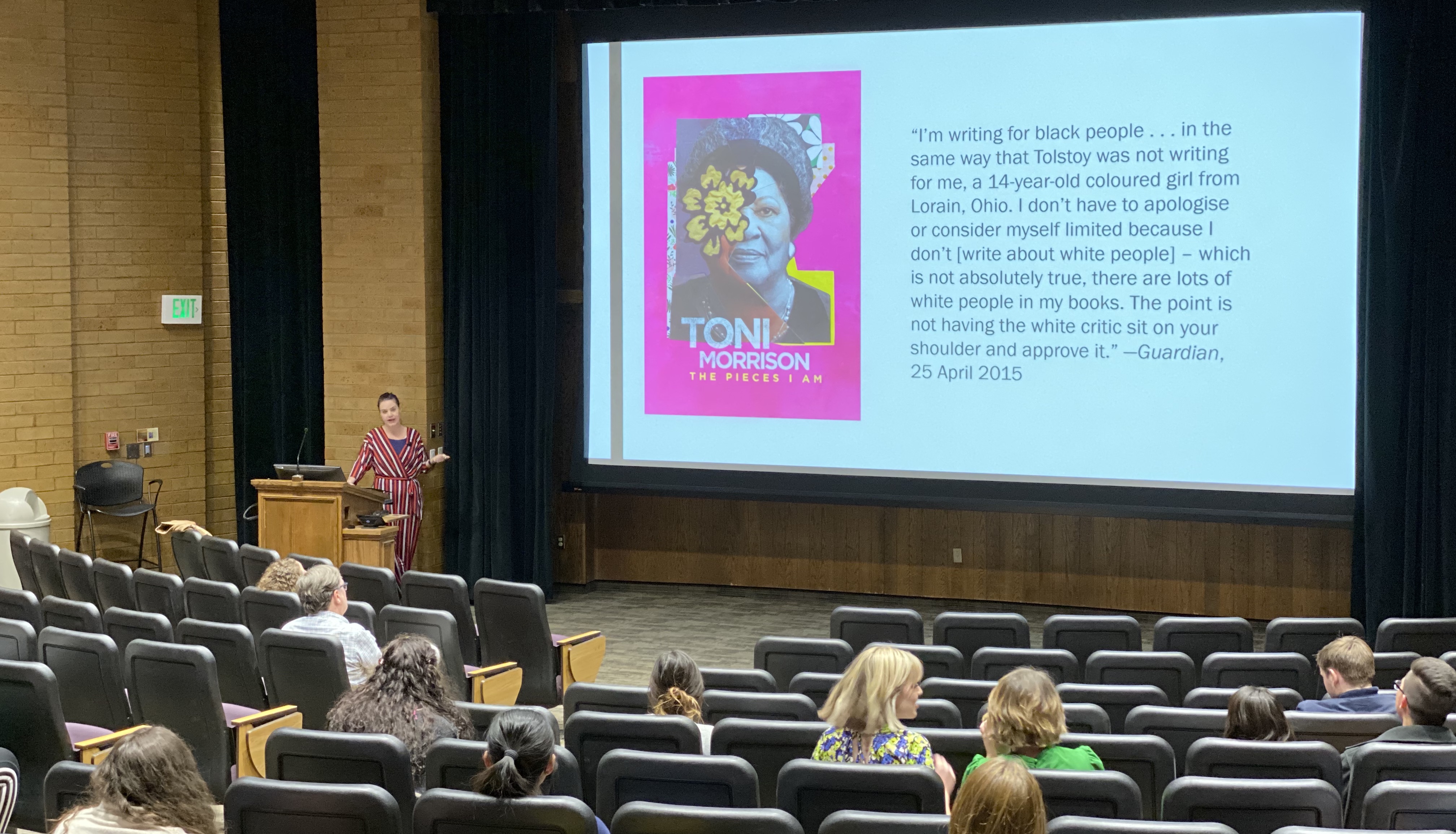

“Racism is racial prejudice plus power,” said Dr. Kristin Matthews of the Department of English. Matthews gave a lecture before a screening of Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am (2019) and touched on two other films in our Representing Race series: Green Book (2018) and If Beale Street Could Talk (2018).

She began with a short overview of some of the ways people of color have been represented and marginalized in American film history. Early American cinema showed blackness in a very limited way, usually through caricatures. Classic films like Birth of a Nation (1915) showed people of color as being criminalistic, savage, and violent. They were presented as threats to society, the nation, and white women specifically. A typical stereotype was the “bumbling, ignorant negro” who is used as comic relief in movies such as Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Judge Priest (1934) or for black women, characters like Mammy (Hattie McDaniel) in Gone With the Wind (1939), a house slave to a wealthy white family to whom she shows great affection. “The Wise Negro” is yet another stereotype of black people in American film in which an older, black person gives sage advice to the struggling white protagonist without any desires for themselves. Films like Driving Miss Daisy (1989) and The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000) employ this trope to paint black people as a tool or mechanism rather than as fully realized human characters. These and other stock characters were continually used to subjugate people of color and to reinforce race relations in terms of white supremacy: an instance of racial prejudice being elevated with power.

Another common and persistent representation of blackness in film was through blackface. Blackface is when a non-black person paints their skin to mimic a grotesque caricature of a person of color. We see this in such famous films as Othello (1965) and The Jazz Singer (1927). Blackface is used as a sort of power fantasy by non-blacks to reinforce harmful stereotypes.

People of color have also been mistreated by the American film industry through the “White Saviour” narrative. This is when a white character saves the black characters or helps them to understand what it is to be black, thus giving power again to white people and subjugating black individualism and power. Some examples of “White Saviour” films include The Help (2011) and Green Book (2018). Contrary to reality, racism in these films is presented as a personal problem. A few bad apples of extreme racism in these films make white viewers (who may not understand how their privilege has benefitted them) feel safe, secure, and certainly not racist themselves. These stereotypes also double down on white supremacist notions of power consolidation under whiteness as ultimately beneficial for people of color.

The author Toni Morrison wrote in this world of stereotypes which were—and are—prevalent in both film and literature. She challenged these notions of blackness as lesser-than in her own writing and in her work as an editor. “She published books that were deliberately black,” according to Matthews, and her work “corrects false stories and offers a range of black individuals” as opposed to the white imagination of blackness and black people as monolithic.

Matthews left the audience with a number of questions to ask oneself when watching a film that may help to recognize the degree to which blackness is being fairly represented. Who benefits from the film? Who makes money off of this production? Does it maintain the status quo or challenge systemic institutional oppression? Who is empowered? Are the people of color characters or caricatures? And, does the film work to make white audiences comfortable?